If you read the label of a fake egg product called JUST Egg, you’ll find an odd ingredient name – transglutaminase.

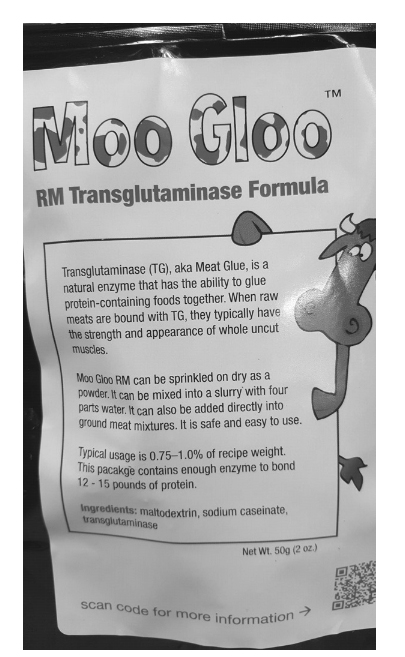

This enzyme, also called “meat glue,” works by bonding proteins together. In the past it was manufactured using the clotting agent extracted from the blood of pigs or cows, but now it’s mostly secreted from microbes. And imitation eggs aren’t the only use to which transglutaminase is put to by the food-processing industry. Others include gluing scraps of meat together to produce an expensive-looking steak, allowing fake fish to look like sushi, improving the texture of dairy products and even increasing a product’s shelf life. No wonder Big Food loves it.

But some researchers are warning that what makes transglutaminase do its job so well with food products may also allow it to promote or encourage celiac disease and other autoimmune conditions, as well as contribute to millions of cases of food poisoning in the U.S. each year.

A double health threat

Transglutaminase can be used by restaurants and manufacturers to get away with a nearly undetectable form of food fraud. By sprinkling the enzyme on various scrap pieces of meat, chicken or seafood, and then binding them in plastic wrap for several hours, they can turn out a picture-perfect “filet mignon” or filet of fish that even an expert wouldn’t know isn’t the real McCoy.

But fakery aside, meat glue could very well be the source of some of those “unaccountable” food-poisoning outbreaks we so often read about. That’s because pathogens such as E. coli, Listeria and Salmonella mostly appear on the surface of meat and are effectively killed by conventional cooking. When multiple pieces are combined, some of those pathogens are moved to the center of the product, lurking in the middle where high temperatures don’t reach them.

But there’s more. A 2018 published study by researchers from the Kipp Institute in Germany and the B. Rappaport School of Medicine in Israel calls transglutaminase a “primary candidate as a partner for CD (celiac disease) development.”

The authors point to several ways in which transglutaminase can trigger an immune reaction leading to celiac disease, one being that the transglutaminase enzyme can alter the structure of gluten peptides making it “likely to resist further breakdown and to be recognized as ‘foreign’” by immune receptors in the gut. Also problematic is the fact that transglutaminase is “structurally different (from) but functionally imitates” tissue transglutaminase (tTG), which is found naturally in the human body. (Those who suffer from celiac disease often produce antibodies that attack tTG).

In 2015 the same authors published a study identifying transglutaminase as one of the common food additives likely behind the “rising incidence of autoimmune disease,” conditions that include not just celiac disease but diabetes, multiple sclerosis and lupus.

More than meat

Novozymes, a UK company, advertises its transglutaminase product for low-fat yogurt to get that creamy texture and taste. Another manufacturer of the enzyme, a company called Siveele, lists dairy and even bakery products among those to which it is added, claiming that its “natural,” cost effective and can be used in products that sport a “clean label.”

Typically, a clean label means that undesirable additives are not mentioned on a product’s ingredient panel. For example, since MSG is undesirable, “clean label” flavor-enhancers such as hydrolyzed pea protein, autolyzed yeast, and soy protein isolate are used instead of MSG. The list of “clean label” ingredients can be found at: https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/ingredient_names.pdf.

On “formed” meat products sold in supermarkets in the U.S. the enzyme must be called out on the ingredient statement (as it is for JUST Egg). It appears that for any other use transglutaminase can go unidentified.

The 2018 study mentioned above states that transglutaminase is “unlabeled and hidden from the public knowledge,” and our attempts to find out exactly where it may be hidden in processed foods sold in the U.S. were largely unsuccessful. Ajinomoto, which is a major producer of transglutaminase as well as MSG, states that in the EU “specific labeling is unnecessary.”

Despite all the uncertainties involved with the labeling of transglutaminase there are things you can do to steer clear of it:

- When dining out, beware of typically expensive menu items that are priced so low they seem too good to be true. Restaurants have no responsibility whatsoever to inform you if they are using transglutaminase.

- If you’re going to eat sushi, do so at a reliable restaurant that specializes in it. Sushi is an expensive and very skilled dish to prepare.

- Low and no fat dairy products have taste and texture problems that might be “solved” by using transglutaminase and are best avoided. Manufacturers try to make up for that issue using things such as flavorings, milk powder and possibly transglutaminase. And as always, keep in mind that the more processed a food item is, the more chance there is that it will contain or be manufactured using a variety of chemicals, additives and enzymes — like transglutaminase.

If you have questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you. If you have hints for others on how to avoid exposure to MfG, send them along, too, and we’ll put them up on Facebook. Or you can reach us at questionsaboutmsg@gmail.com and follow us on Twitter @truthlabeling.