Introduction

In the well-researched article, “Emerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of Gulf War illness (GWI),” substantial evidence is presented demonstrating that Gulf War-related agents and traumatic stress (Gulf War-related exposures) affect glutamate transmission in the brain (1).

Named as examples of Gulf War-related chemical agents were pyridostigmine bromide (given to soldiers as an anti-nerve agent pretreatment), sarin nerve agent, pesticides, and smoke from burning oil wells.

Also named were the commonly reported symptoms of veterans identified as suffering with GWI, which include mood problems, cognitive impairment, muscle and joint pain, migraine headache, chronic fatigue, gastrointestinal complaints, skin rashes, and respiratory problems.

Encouraged by growing evidence indicating that abnormal glutamate neurotransmission may contribute to the GWI symptoms, the authors summarized the potential roles of glutamate dyshomeostasis and dysfunction of the glutamatergic system in linking the initial cause to the multi-symptomatic outcomes in GWI and suggested the glutamatergic system as a therapeutic target for GWI.

Their research did not, however, take into account the fact that those deployed to the Gulf War were consuming excitotoxic chemicals in their food on a daily basis. The authors failed to realize that food being fed to those deployed to the Gulf War contained neurotoxic chemical agents just as the Gulf War environment did, and that review of relevant literature would demonstrate that the excitotoxic manufactured free glutamate (MfG), present in quantity in processed food could cause and/or exacerbate GWI.

A May 2021 search of PubMed for Gulf War Illness returned 730 articles, 622 of which made no mention of glutamate. Of the eight others, only one came close to associating glutamate with food consumed by service men and women in the combat zone, but even that study focused on the value of a low-glutamate diet as treatment for the injured, not as a possible means of prevention (2). No study of GWI cited on PubMed considered the possibility that those on the front lines were consuming excitotoxic chemicals in processed foods on a daily basis.

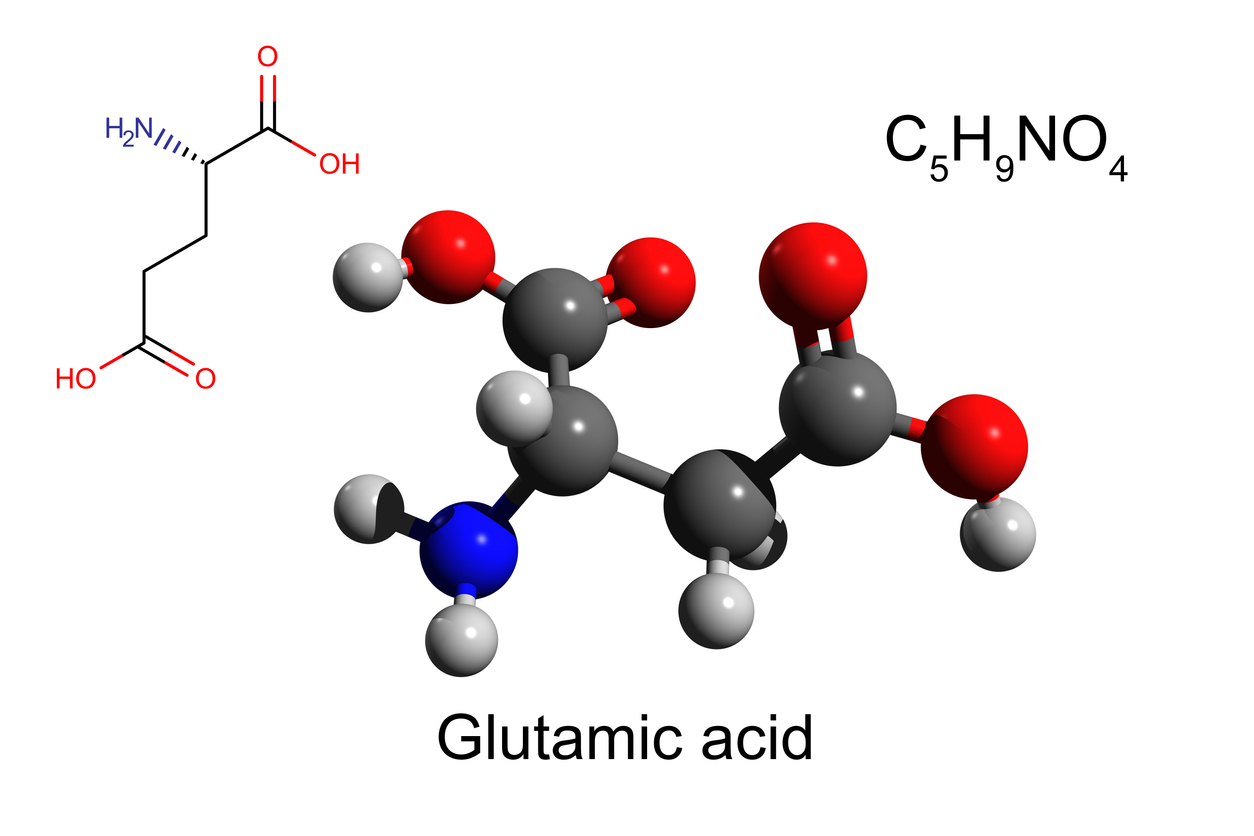

Glutamate as an excitotoxic amino acid

Evidence that glutamate is an excitotoxic amino acid is well understood by neuroscientists. In 1969, Olney published results of the first study that demonstrated that glutamate administered to laboratory animals caused brain lesions in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus as well as other areas of the brain, with brain damage followed by obesity, behavioral abnormalities and reproductive dysfunction (3). And Olney coined the term “excitotoxin” to explain the phenomenon. At the time, researchers were administering glutamate to laboratory animals subcutaneously using Accent brand MSG because it had been observed that the product was as effective for inflicting brain damage as more expensive pharmaceutical grade L-glutamate (3). The glutamate administered would have been made up of both L-glutamate (the glutamate enantiomer with flavor-enhancing potential) and D-glutamate (an unwanted by-product accompanying the manufacture of the L-glutamate manufactured for use in MSG).

L-glutamate is the L enantiomer of glutamic acid (glutamate), an acidic amino acid which when present in protein or released from protein in a regulated fashion (through routine digestion) is vital for normal body function. It is the principal neurotransmitter in humans, carrying nerve impulses from glutamate stimuli to glutamate receptors throughout the body. Yet, when present outside of protein in amounts that exceed what the healthy human body was designed to accommodate (which can vary widely from person to person), glutamate becomes an excitotoxic neurotransmitter, firing repeatedly, damaging targeted glutamate-receptors and/or causing neuronal and non-neuronal death by over exciting those glutamate receptors until their host cells die (4-9).

Throughout the 1970s, researchers confirmed that glutamate induces hypothalamic damage when given to immature animals after either subcutaneous or oral doses (10).

In the 1980s, researchers focused on identifying and understanding abnormalities associated with glutamate, often for the purpose of finding drugs that would mitigate glutamate’s adverse effects. It is well documented that L-glutamate is implicated in kidney and liver disorders, neurodegenerative disease, and more. By 1980, glutamate-associated disorders such as headaches, asthma, diabetes, muscle pain, atrial fibrillation, ischemia, trauma, seizures, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, depression, multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), epilepsy, addiction, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), frontotemporal dementia and autism were on the rise, and evidence of the toxic effects of glutamate were generally accepted by the scientific community. A November 15, 2020 search of the National Library of Medicine using PubMed.gov returned 3872 citations for “glutamate-induced.”

By and large, the glutamate in question was, and still is, glutamate from endogenous sources. The possible toxicity of glutamate from exogenous sources such as glutamate-containing protein substitutes and glutamate-containing flavor enhancers has generally not been considered. Only Olney and a few others have suggested that ingestion of free glutamate might play a role in producing the excess amounts of glutamate needed for endogenous glutamate to become excitotoxic (11).

Additional evidence of the toxicity of glutamate from exogenous sources such as eating, comes from studies undertaken by the producer of MSG to convince the public that MSG is a harmless food additive. Detail of how studies were systematically designed to produce negative results (no harm found) is elaborated in supplemental files at the end: 1 (The Toxicity/Safety of Processed Free Glutamic Acid (MSG): A Study in Suppression of Information), 2 (Designed for Deception), and 3 (The Alleged Safety of Monosodium Glutamate (MSG).

The success of glutamate-industry double-blind studies that always produced negative results (no MSG-induced damage demonstrated) can be attributed, at least in part, to use of “placebos” containing undisclosed excitotoxic amino acids that cause reactions identical to those caused by MSG test material.

The single greatest obstacle to transparency of the dangers of MSG has been the FDA’s 50-year allegiance to Ajinomoto, the U.S. manufacturer of MSG, with the FDA maintaining that MSG, a product never tested for safety, is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) while simultaneously parroting Ajinomoto’s misleading statements and downright lies. During the 1990s, that relationship was harmonized by the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (SFSAN), Fred Shank (deceased) being CFSAN director at the time. As Director of CFSAN, Shank led the development of policies and programs focused on consumer protection, including the implementation of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, the most comprehensive food labeling legislation in U.S. History. And he refused to include consideration of the toxicity of MSG in that legislation. Also notably influential at that time on behalf of the alleged safety of MSG was Linda Tollefson, Associate Commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine (retired).

Those familiar with adverse reactions following ingestion of MSG, whose essential component is excitotoxic – brain damaging — free glutamic acid (MfG), understand that MfG affects each individual differently, with multiple organ systems involved including the nervous system, digestive system, and respiratory system. Similar to reports of GWI symptoms, symptoms reported by MSG-sensitive people include fatigue, joint pain, memory loss, sleep difficulties, headaches, concentration loss, depression and anxiety, skin rashes, gastrointestinal problems, and breathing problems, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Table 2 lists reactions reported following ingestion of MSG and the other ingredients that contain MfG. For a short time, the FDA also maintained a list of adverse reactions to MSG in their Adverse Reactions Monitoring System. These were unsolicited reports kept before the FDA decided that “there was no point to keeping such records because the FDA knew that virtually no one was sensitive to MSG (12).”

The wide variety in GWI symptomatology provides the clue to identifying at least one cause of GWI.

Pharmaceuticals come with package inserts that list the side effects known to occur in some people following administration. The reactions listed in those package inserts are as varied as reactions known to occur following ingestion of MfG. (Different pharmaceuticals produce different side effects in different people. MSG produces different side effects, a.k.a. adverse reactions, in different people.) No surprise here, for when used in food, glutamate is called a food and when used in pharmaceuticals, the same glutamate is called a drug. The symptoms expressed individually by GWI veterans are all symptoms that occur to some consumers following ingestion of MfG.

Aside from a pair of studies that demonstrated a low-glutamate diet reduced multiple symptoms of GWI (13,14) there has not been even a hint in the medical literature that ingestion of MfG in the food available to Gulf War forces might have contributed to GWI.

It comes as no surprise to those of us who have dealt on a daily basis with the adverse reactions caused by MfG, that the military would be unaware of its relevance to GWI, for beginning in 1969 with the first evidence of glutamate excitotoxicity, information pertaining to glutamate toxicity has been systematically suppressed. Since 1991, no major U.S. media have carried so much as a hint that MSG, the best-known of the ingredients that contain MfG, might be anything more than controversial. And few researchers in the U.S. broached the subject of glutamate-toxicity prior to the relatively new research cited here that has suggested or demonstrated a link between glutamate and GWI (1,13-18).

Since 1988, when George Schwartz, M.D. published “In Bad Taste: the MSG Syndrome,” (19) the U.S. manufacturer of MSG has been engaged in dissemination of deceptive and misleading information that hypes the safety of their product.

That includes the MSG-is-safe research double-blind studies systematically designed to produce negative studies (no MSG-inflicted harm found) which always included, among other things, the use of placebos containing excitotoxic amino acids known to cause reactions identical to those caused by MSG.

In discussing the suppression of information about the excitotoxicity of free glutamate, we would be remiss in not addressing the subject of “authoritative bodies” who have said that MSG and the glutamate in it are safe for human consumption. Recently mentioned in glutamate-industry material as organizations on record as having reviewed the safety of MSG and found it to be a harmless food additive were Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), the New South Wales Government Food Authority in Australia, the American Medical Association and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Those organizations did no research of their own, either in the laboratory or the library, but reviewed material brought to them by the U.S. manufacture of MSG, the FDA, or others such as Andrew Ebert, Ph.D. the “scientist” in charge of MSG-is-safe research prior to the time he was exposed for overseeing use of excitotoxic amino acids in double-blind study placebos. Ebert distributed both test materials and material that he called placebos (allegedly inert substances that could not possibly cause a physical reaction in a person who ingested them) for use in double-blind studies designed to demonstrate that MSG is safe.

The only question about the role that glutamate plays in cause or exacerbation of GWI that remains to be addressed here has to do with availability of sufficient free glutamate to cause the free glutamate present to express excitotoxicity. At one time it would have been meaningful to note that the amount of excitotoxic material in a particular ingredient would not be sufficient to cause brain damage or adverse reactions. But since the 1957 change in method of MSG production, there are so many products that contain manufactured free glutamate and other excitotoxins that it is easy for a consumer to ingest an excess of excitotoxic material during the course of a day (20-24).

Prior to 1957, the amount of free glutamate or other excitotoxic additives in the average U.S. diet had been unremarkable. During that year, however, the method of producing the free glutamate that makes up the excitotoxic portion of MSG changed from extraction of glutamate from a protein source, a slow and costly method, to a process of bacterial fermentation (25). This allowed virtually unlimited production of free glutamate and MSG.

It didn’t take long for industry to add dozens more excitotoxic food additives to the American diet. Following MSG’s surge in production and aggressive advertising, it was realized that profits could be significantly increased if companies produced their own flavor-enhancing additives. Since that time, the market has been flooded with flavor enhancers and protein substitutes that contain MfG such as hydrolyzed proteins, yeast extracts, maltodextrin and soy protein isolate, as well as MSG. (See table 3). To that has been added the toxic load contributed by excitotoxic aspartic acid, approved by the FDA for use in aspartame, equal, and related products starting in 1974. The excitotoxins in aspartic acid and glutamic acid act in an additive fashion.

Soon after use of genetically modified bacteria in the production of MSG began, availability of MSG and other MfG-containing products increased to the point where there was more than sufficient MfG to become excitotoxic if a number of processed and ultra-processed foods were consumed during the course of a day. And an environment full of war-related toxic chemical agents would be likely to enhance a soldier’s vulnerability.

Summary

There was sufficient manufactured free glutamate in processed foods served to Gulf War service members to serve as an excitotoxic – brain damaging – chemical, causing or exacerbating GWI.

References

1. Wang X, Ali N, Lin C. Emerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of Gulf War illness. Life Sci. 2021 May 12: 119609.

2. Joyce MR, Holton KF. Neurotoxicity in Gulf War Illness and the potential role of glutamate. Neurotoxicology. 2020;80:60-70.

3. Olney JW. Brain lesions, obesity, and other disturbances in mice treated with monosodium glutamate. Science. 1969;164(880):719-721. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5778021/

4. Excitotoxicity and cell damage https://www.sciencedaily.com/terms/excitotoxicity.htm

5. Ischemia-Triggered Glutamate Excitotoxicity From the Perspective of Glial Cells https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2020.00051/full

6. Hernández DE et al. Axonal degeneration induced by glutamate excitotoxicity is mediated by necroptosis. J. Cell Sci. 2018 Nov 19;131(22):jcs214684.

7. Garzón F et al. NeuroEPO preserves neurons from glutamate-induced excitotoxicity J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018;65(4):1469-1483.

8. Zárate SC, Traetta ME, Codagnone MG, Seilicovich A Reinés AG.

Humanin, a mitochondrial-derived peptide released by astrocytes, prevents synapse loss in hippocampal neurons. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019 May 31;11:123.

9. Plitman E et al. Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in schizophrenia: a review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1591-1605.

10. Studies demonstrating both glutamate and MSG-induced brain damage https://www.truthinlabeling.org/Data%20from%20the%201960s%20and%201970s%20demonstrate_2.html

11. Alerts from independent researchers outside of the United States, warning of the dangers posed by ingesting MSG https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/researchers_warnings.pdf

12. Summary of adverse reactions attributed to MSG https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/arms_msg.pdf

13. Joyce MR, Holton KF. Neurotoxicity in Gulf War Illness and the potential role of glutamate. Neurotoxicology. 2020 Sep;80:60-70.

14. Holton KF, Kirkland AE, Baron M, Ramachandra SS, Langan MT, Brandley ET, Baraniuk JN. The Low Glutamate Diet Effectively Improves Pain and Other Symptoms of Gulf War Illness. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 26;12(9):2593.

15. Wang X, Xu Z, Zhao F, Lin KJ, Foster JB, Xiao T, Kung N, Askwith CC, Bruno JP, Valentini V, Hodgetts KJ, Lin CG. Restoring tripartite glutamatergic synapses: A potential therapy for mood and cognitive deficits in Gulf War illness. Neurobiol Stress. 2020 Jul 13;13:100240.

16. Macht VA, Woodruff JL, Burzynski HE, Grillo CA, Reagan LP, Fadel JR. Interactions between pyridostigmine bromide and stress on glutamatergic neurochemistry: Insights from a rat model of Gulf War Illness. Neurobiol Stress. 2019 Dec 31;12:100210.

17. Gargas NM, Ethridge VT, Miklasevich MK, Rohan JG. Altered hippocampal function and cytokine levels in a rat model of Gulf Warillness. Life Sci. 2021 Jun 1;274:119333.

18. Torres-Altoro MI, Mathur BN, Drerup JM, Thomas R, Lovinger DM, O’Callaghan JP, Bibb JA. Organophosphates dysregulate dopamine signaling, glutamatergic neurotransmission, and induce neuronal injury markers in striatum. J Neurochem. 2011 Oct;119(2):303-13.

19. Schwartz GR. In Bad Taste: the MSG Syndrome. Santa Fe: Health Press, 1988.

20. Hashimoto S. Discovery and History of Amino Acid Fermentation. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2017;159:15-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27909736/

21. Sano C. History of glutamate production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):728S-732S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19640955/

22. Market Research Store. Global Monosodium Glutamate Market Poised to Surge from USD 4,500.0 Million in 2014 to USD 5,850.0 Million by 2020. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2016/03/17/820804/0/en/Global-Monosodium-Glutamate-Market-Poised-to-Surge-from-USD-4-500-0-Million-in-2014-to-USD-5-850-0-Million-by-2020-MarketResearchStore-Com.html (Accessed 5/29/2020)

23. Open PR Worldwide Public Relations for Verified Market. Global Flavor Enhancers Market. https://www.bccresearch.com/partners/verified-market-research/global-flavor-enhancers-market.html (Accessed 5/29/2020)

24. Dataintelo. Global Food Flavor Enhancer Market Report, History and Forecast 2014-2025, Breakdown Data by Manufacturers, Key Regions, Types and Application. https://dataintelo.com/report/food-flavor-enhancer-market (Accessed 5/29/2020)

25. Khan IA, Abourashed EA. Leung’s Encyclopedia of common natural ingredients used in food, drugs, and cosmetics (Third Edition). New Jersey: Wily, 2010. Pp 452-455. https://naturalingredient.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/leungs-encyclopedia-of-common-natural-ingredients-3rd-edition.pdf

Tables

Table 2: Adverse reactions known to be caused from time to time by MSG and the other ingredients that contain MfG

https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/reactions_list2.pdf

Table 3: Names of ingredients that contain Manufactured free Glutamate (MfG) (Updated May 2021)

https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/ingredient_names.pdf

Supplemental material

File 1. The Toxicity/Safety of Processed Free Glutamic Acid (MSG): A Study in Suppression of Information

https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/manuscript2.pdf

File 2. The Alleged Safety of Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)

https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/review_studies.pdf

File 3. Designed for Deception: The fail-safe way to ensure that their studies would conclude MSG is harmless

https://www.truthinlabeling.org/assets/designed_for_deception_short.pdf