In case you didn’t know, excitotoxic – brain damaging — free glutamate is an essential ingredient in all ultra-processed food. You may recognize it as the essential ingredient in monosodium glutamate (MSG) – which is itself an ultra-processed food.

Fake foods: how to quickly spot them

We’ve told you about fake fish, meat and eggs, all disguised to look like the real thing. And despite all the extravagant claims made by manufacturers, if you read the ingredient labels on these products you’ll find that they are not eggs, meat or fish, and not the kinds of “plants” grown by farmers either. As we’ve said before, a better name might be chemical-based junk foods.

Reading labels is vital, but there’s one tip that can save you some time in the supermarket:

Watch out for products that make protein claims on the packaging. Most are made from combinations of manufactured free amino acids such as those found in MSG and in aspartame. This includes snack bars, cookies, smoothie mixes, protein powders and protein drinks in addition to fake eggs, fish, and meat.

All, “substitute” protein products will contain MSG and its toxic component free glutamate.

Remember also that soy, pea and bean protein do not taste remotely like meat, fish or eggs, so free glutamate flavor enhancers like MSG are added to trick your tongue into making that taste association.

Check out our list of ingredient names that contain free glutamate as well as our brochure to take shopping with you. Better yet, if you want to do all you can to have a healthy diet, ditch the processed foods and ultra-processed fake foods, altogether.

Challenge: Find the plants in these ‘plant-based’ products!

The latest and greatest “foods” to hit restaurants and grocery store shelves these days are made from plants — or so we’ve been told. With that advertising claim in mind, we challenge you to find the plants in these products. The ingredients listed below are for the Impossible Burger, Beyond Burger, and Just Egg.

Some of the ingredients that contain free glutamate — the toxic ingredient found in MSG — have been highlighted for you. Maybe they qualify as plant based. They are made in food processing and/or chemical plants.

Once you take a look at what these products are made from it will be obvious that they’re not meat, they’re not eggs, and they’re not the kinds of plants grown by farmers. A better name might be chemical-based junk foods.

Impossible Burger

Water, Soy Protein Concentrate, Coconut Oil, Sunflower Oil, Natural Flavors, 2% or less of: Potato Protein, Methylcellulose, Yeast Extract, Cultured Dextrose, Food Starch Modified, Soy Leghemoglobin, Salt, Soy Protein Isolate, Mixed Tocopherols (Vitamin E), Zinc Gluconate, Thiamine Hydrochloride (Vitamin B1), Sodium Ascorbate (Vitamin C), Niacin, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride (Vitamin B6), Riboflavin (Vitamin B2), Vitamin B12.

https://faq.impossiblefoods.com/hc/en-us/articles/360018937494-What-are-the-ingredients-

Beyond Burger Patties

Ingredients: Water, pea protein isolate, expeller-pressed canola oil, refined coconut oil, rice protein, natural flavors, cocoa butter, mung bean protein, methylcellulose, potato starch, apple extract, salt, potassium chloride, vinegar, lemon juice concentrate, sunflower lecithin, pomegranate fruit powder, beet juice extract (for color)

https://www.beyondmeat.com/products/the-beyond-burger/

Just Egg

Ingredients: Water, Mung Bean Protein Isolate, Expeller-Pressed Canola Oil, Contains less than 2% of Dehydrated Onion, Gellan Gum, Natural Carrot Extractives (color), Natural Flavors, Natural Turmeric Extractives (color), Potassium Citrate, Salt, Soy Lecithin, Sugar, Tapioca Syrup, Tetrasodium Pyrophosphate, Transglutaminase, Nisin (preservative). (Contains soy.)

MSG, the secret ingredient that makes a pet food a ‘success’

For most pet owners, the proof of quality, flavorful pet food products is in watching our furry friends enjoy their food. When a new diet is introduced to a pet and it stimulates active consumption, it’s considered palatable, and therefore a success. — Kemin Industries

Your idea of a successful food for your pet is probably one that will nourish your pup or kitty and help them live a long, healthy life. But for pet food companies, success is measured by how quickly a dog or cat eagerly eats up every last bite of the same food every single day.

Palatability is a key phrase in the industry. And to ensure that the food is palatable, or tasty and appetizing to the pet, a “secret” ingredient is added — one called a “palatant.”

Palatants are big business. These additives coerce an animal into consuming what’s placed in front of it (even if it’s an unappetizing-looking bowl of hard, brown pellets) using exactly the same method that makes Cheetos irresistible or gets Doritos to taste like the most delicious thing you’ve ever put in your mouth. You know the secret ingredient as monosodium glutamate (MSG), but it’s really the free glutamate in the MSG that triggers our taste buds and our animals’ taste buds, making them beg for more. Free glutamate can be found in 40+ food ingredients.

Palatants, which are also called “digests,” are primarily made from either hydrolyzed animal or vegetable proteins, which invariably contain free glutamate. When a protein is hydrolyzed it will always create excitotoxic – brain damaging — amino acids. It doesn’t matter if that hydrolyzed protein is put in dog food or a can of tuna you eat for lunch, it will contain free glutamate, the brain-damaging ingredient found in MSG.

Now, if you plan to carefully examine the labels of pet foods for this noxious ingredient, you won’t come away with much information. Palatants can be listed on the label as “natural flavoring,” “digest,” or simply incorporated into some other benign-sounding component of the food – both in bargain brands and pricy boutique ones.

There are, however, some pet foods that will tell you right on the package that they’re using free glutamate-containing hydrolyzed proteins.

The pea-protein gravy train

Currently, the biggest darling of the food industry is widespread, multi-purpose pea protein. It’s a cheap ingredient used to bump up protein content in scores of bars, drinks, powders for smoothies and fake foods. Read more about it here.

When used in pet food, it’s advertised as an easily digestible source of protein, and is typically found in allergy, grain-free and limited protein diets.

Purina is one of many major pet food manufacturers that uses pea protein in its dog food formulas. While consumers are starting to realize that pea protein in human foods contains excitotoxic, brain-damaging free glutamate, it appears that same level of concern doesn’t apply to what we feed our pets. That is, until we learn that something has gone terribly wrong.

The mysterious heart ailment associated with grain-free pet foods

In 2018 the FDA issued an alert about grain-free pet food being implicated in untold numbers of otherwise healthy dogs and cats developing dilated cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle that can come on slowly and ultimately be fatal.

In typical FDA slow-motion style, the agency first received reports of the potential connection back in 2014, yet waited four years to warn pet owners. Now we know that all breeds, ages and sizes of dogs have been involved in the 560 accounts the FDA received (which most certainly are only a fraction of the actual number of cases).

Interestingly, no heavy metal compounds were found in the foods tested, but over 90 percent of the food consisted of grain-free formulas containing pea and/or lentil protein, i.e., free glutamate.

Could the excitotoxic amino acids in those ingredients have triggered this deadly heart condition? It’s pretty much a given that we will never learn more from the FDA. To even consider these highly processed, toxic vegetable proteins as a potential cause of this tragedy is something that agency will never, ever do.

The U.S. pet food industry is predicted to reach $30 billion in the next two years, with more and more expensive, highly advertised and “gourmet” brands on the market. Despite all the glowing package claims and pictures of fish, meat and poultry, the contents generally consist of low-quality, toxic ingredients.

And sadly, our dogs and cats are becoming overweight, morbidly obese, diabetic and sick at an ever-increasing rate – just as are their human companions.

Snake in the GRAS

When you hear that the FDA considers monosodium glutamate GRAS – or, generally recognized as safe – what does that mean? It’s certainly one of the “selling points” that industry likes to toss around a lot as evidence that monosodium glutamate is harmless.

But that GRAS designation is inherently deceiving.

Sixty-two years ago, following passage of the Food Additives Amendment of 1958, the FDA grandfathered monosodium glutamate into a category of additives called GRAS. There was no testing done or even reviewed by the FDA to determine if monosodium glutamate was indeed safe. The GRAS classification was solely based on monosodium glutamate having been in use without objection prior to 1958. The actual safety of pre-1958 monosodium glutamate was not then, and never has been, established.

But to make using a GRAS label for monosodium glutamate even more farfetched, is the fact that the monosodium glutamate in use in the U.S. today is not even the same as the monosodium glutamate that was grandfathered as GRAS in 1958. From 1920 until 1956, the process underlying production of glutamic acid and monosodium glutamate in Japan had been one of extraction, a slow and costly method (1). Then, around 1956, Ajinomoto Co., Inc. succeeded in producing glutamic acid and monosodium glutamate using genetically modified bacteria to secrete the glutamic acid used in monosodium glutamate through their cell walls, and cost saving, large-scale production of glutamic acid and monosodium glutamate through fermentation began (2,3).

Approximately ten years later, the first published report of an adverse reaction to monosodium glutamate appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine (4), and a study demonstrating that monosodium glutamate was excitotoxic, causing brain damage, endocrine disorders and behavior disorders, was published in the journal Science in 1969 (5). Of interest to note is the fact that by the time ten years had gone by, grocery shelves were overflowing with processed foods loaded with monosodium glutamate, hydrolyzed protein products, autolyzed yeasts and lots of other ingredients that contained the same toxic free glutamic acid found in monosodium glutamate.

REFERENCES

- Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia. 6th ed. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983:1211-2.

- Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. New York: Wiley, 1978:410-21.

- Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 4th ed. New York: Wiley, 1992:571-9.

- Kwok RHM. The Chinese restaurant syndrome. Letter to the editor. N Engl J Med. 1968;278(14):796.

- Olney JW. Brain lesions, obesity, and other disturbances in mice treated with monosodium glutamate. Science. 1969;164:719-721.

Ultra-processed foods: Little nourishment, lots of toxic amino acids

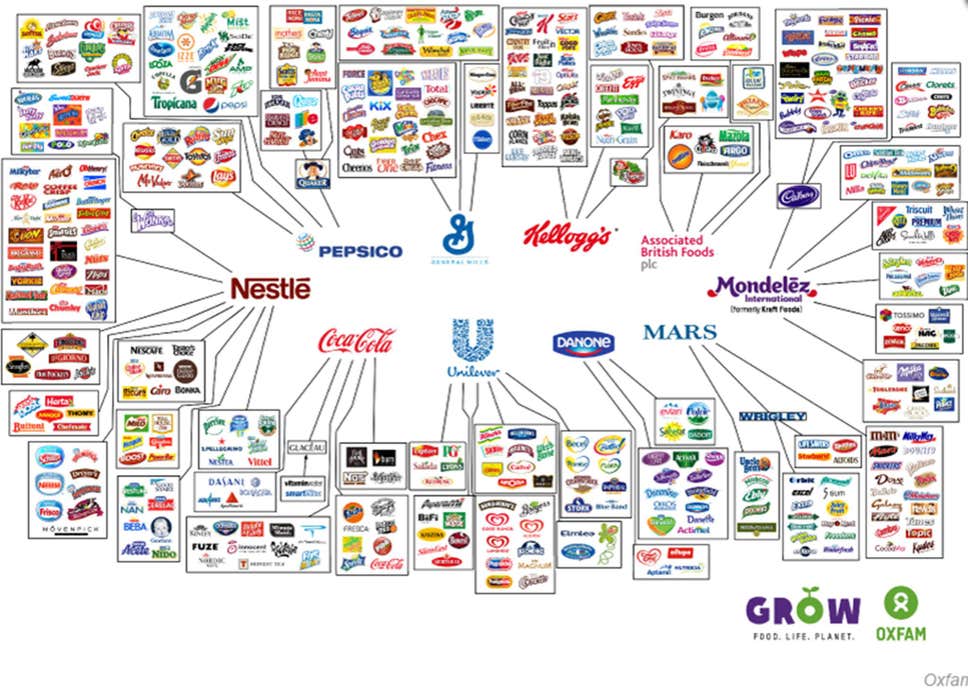

Although the typical U.S. supermarket contains a wide variety of packaged foods, that assortment emanates from 10 giant conglomerates.

These multinationals, such as Unilever, Coca-Cola and Mondelez, have their imprints on practically everything you eat. And more and more of these products are “ultra-processed.”

It used to be that food technologists designed processed foods. Those would be whole foods that were canned, freeze-dried, or fermented, for example. But in the 1980s ultra-processed food — products manufactured with substances extracted from foods or synthesized in laboratories — started to line supermarket shelves.

Ultra-processed foods are fractionated-recombined foods consisting of an extensive number of additives and ingredients, but little actual whole food. They can be identified by the remarkably long list of ingredients – including many unpronounceable ones — found on their labels. According to a recent study, Canadians are taking in practically half of their daily calories from ultra-processed foods.

Not mentioned in any study of ultra-processed foods, however, are the toxic ingredients added for color, flavor, shelf life (preservatives), and protein, along with low-calorie sweeteners. Free glutamate, the toxic component of monosodium glutamate, and all of the ingredients in the following list are found in both flavor enhancers and protein enhancers. And some say because they mask the taste of old or rancid food, free glutamate is used as a preservative as well.

Names of ingredients that always contain free glutamate:

- Glutamic acid (E 620)

- Glutamate (E 620)

- Monosodium glutamate (E 621)

- Monopotassium glutamate (E 622)

- Calcium glutamate (E 623)

- Monoammonium glutamate (E 624)

- Magnesium glutamate (E 625)

- Natrium glutamate

- Anything “hydrolyzed”

- Any “hydrolyzed protein”

- Calcium caseinate, Sodium caseinate

- Yeast extract, Torula yeast

- Yeast food, Yeast nutrient

- Autolyzed yeast

- Gelatin

- Textured protein

- Whey protein

- Whey protein concentrate

- Whey protein isolate

- Soy protein

- Soy protein concentrate

- Soy protein isolate

- Anything “protein”

- Anything “protein fortified”

- Soy sauce

- Soy sauce extract

- Protease

- Anything “enzyme modified”

- Anything containing “enzymes”

- Anything “fermented”

- Vetsin

- Ajinomoto

- Umami

- Zinc proteninate

Names of ingredients that often contain or produce free glutamate during processing:

- Carrageenan (E 407)

- Bouillon and broth

- Stock

- Any “flavors” or “flavoring”

- Natural flavor

- Maltodextrin

- Oligodextrin

- Citric acid, Citrate (E 330)

- Anything “ultra-pasteurized”

- Barley malt

- Malted barley

- Brewer’s yeast

- Pectin (E 440)

- Malt extract

- Seasonings

The following are ingredients suspected of containing or creating sufficient processed free glutamate to serve as reaction triggers in HIGHLY SENSITIVE people:

- Corn starch

- Corn syrup

- Modified food starch

- Lipolyzed butter fat

- Dextrose

- Rice syrup

- Brown rice syrup

- Milk powder

- Reduced fat milk (skim; 1%; 2%)

- most things “low fat” or “no fat”

- anything “enriched”

- anything “vitamin enriched”

- anything “pasteurized”

- Annatto

- Vinegar

- Balsamic vinegar

- certain amino acid chelates (Citrate, aspartate, and glutamate are used as chelating agents with mineral supplements.)

Convenient, relatively inexpensive and heavily advertised, the future of ultra-processed foods seems to be assured (1). And why not? The FDA lets the people who manufacture ultra-processed foods declare that they are GRAS (generally recognized as safe), and the general public seems unaware that the fox is guarding the hen house.

Reference

1. Open PR Worldwide Public Relations. Press release. 7/3/2019. “What’s driving the Flavor Enhancers Market Growth? Cargill, Synergy Flavors, Tate & Lyle, Associated British Foods pic, Corbion …” https://www.openpr.com/news/1794737/what-s-driving-the-flavor-enhancers-market-growth-cargill. Accessed 7/31/2019.

Just Say NO

Say “no” to brain damage caused by manufactured free glutamate. Check out the names of ingredients that contain it: https://www.truthinlabeling.org/names.html

Everything you need to know about glutamate before your next trip to the supermarket

Glutamic acid (glutamate) is a building block of protein. When present in protein or released from protein in a regulated fashion, glutamate is vital to normal body function. It is the major neurotransmitter in the human body, carrying nerve impulses from glutamate stimuli to glutamate receptors throughout the body. Yet when present outside of protein in amounts that exceed what the healthy human body was designed to accommodate (when present in excess), glutamate takes on excitotoxic properties, becoming an excitotoxic neurotransmitter, firing repeatedly, damaging targeted glutamate-receptors and/or causing neuronal and non-neuronal death by over exciting glutamate receptors until their cells die.

Excitotoxicity of L-glutamic acid (glutamate) was first demonstrated in 1969. On April 3, 2019, a PubMed search for “glutamate” produced 157,021 references. Topics being researched included, but were not limited to, glutamate receptors, transport, excitotoxicity, release, transporter, brain, synthesis, monosodium glutamate, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, ALS, autism, schizophrenia, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), epilepsy, ischemic stroke, seizures, Huntington’s disease, addiction, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism.

Much, if not all of that research dealt with excitotoxicity caused by glutamate from endogenous1 sources. The contribution of glutamate from exogenous2 sources to endogenous glutamate pools through which excitotoxicity would be triggered, seems never to have been considered.

Overlooked also, is a wealth of knowledge that could be gleaned from the histories of humans who have suffered brain damage, endocrine disorders, and observable adverse reactions following intake of excitotoxic glutamate from exogenous sources.

With the following we present an overview of what we know, or think we know, about the function of glutamate in persons who have experienced reactions to it. It is our hope that insights generated by this information may be used by researchers probing the mechanisms of glutamate toxicity, and by the medical professionals working with people who react to the excitotoxic effects of Manufactured free Glutamate.

Vulnerability

Everyone is vulnerable to the toxicity of excitotoxins if they get a heavy enough dose of them. There are no exceptions. To be toxic, an excitotoxin must either target receptors that have become weakened or vulnerable to their attack, or be in such strong concentrations that no glutamate receptor can resist them.

Vulnerability may be created by:

- An inadequate BBB — allowing brain cells to be unprotected by a blood-brain barrier (BBB);

- A damaged BBB;

- Preexisting brain damage, possibly from a stroke, a blow to the head, or previously consuming a large quantity of Manufactured free glutamate at one sitting, and

- Preexisting damage done to cells that host glutamate receptors in either the central nervous system or in peripheral tissue.

We know very little about the actions of excitotoxins. Glutamate loads on (triggers) glutamate receptors both in the central nervous system and in peripheral tissue (heart, lungs, and intestines, for example). When loading on (stimulating) a glutamate receptor, glutamate may simply stimulate receptors and then fade, so to speak; may damage the cells that those receptors cling to; or may stimulate those receptors (over-excite those receptors) until the cells that host them die.

There’s another possibility. There are a great many glutamate receptors in the brain. It is possible that if a few are damaged or wiped out following ingestion of Manufactured free glutamate, their loss may not be noticed because there would be many undamaged glutamate receptors remaining. It is also possible that individuals differ in the numbers of glutamate receptors that they have to begin with; that people with more glutamate receptors are less likely to demonstrate brain damage following ingestion of Manufactured free glutamate because even after some cells are killed or damaged, there are still sufficient undamaged cells to carry out normal functions.

Saying it another way, people with fewer receptors to begin with might be more likely to demonstrate brain damage following ingestion of MSG or MfG because they have fewer glutamate receptors remaining after excitotoxic insult than individuals who had more glutamate receptors to begin with. That might account for some people being more sensitive to Manufactured free glutamate than others.

Less is known about glutamate receptors outside the brain – in the heart, stomach, and lungs, for example. But it would be anticipated that in each location there would be fewer glutamate receptors siting on host cells than found in the brain; and for some individuals, there might be so few cells with glutamate receptors to begin with, that ingestion of even small amounts of Manufactured free glutamate might trigger asthma, atrial fibrillation, or irritable bowel, for example; while individuals with more cells hosting glutamate receptors to begin with, would not notice the loss of a relatively few cells.

Short-term effects of excitotoxic glutamate (effects like asthma and migraine headache) have long been obvious to all who are not swayed by the rhetoric of the glutamate industry and their friends, including friends at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Researchers may only now begin to correlate the adverse effects of glutamate ingestion with endocrine disturbances such as reproductive disorders and gross obesity, with some psychological disorders, and with neurodegenerative disease. And a few have begun to realize the importance of glutamate’s access to the human body through the mouth, through the nose, and through the skin.

Excess

Glutamate is a non-essential amino acid, meaning that there is no need for a human to ingest glutamate as the body will produce what it needs from other available amino acids.

A reaction to glutamate, is a reaction to excess free glutamate. Because of differences in vulnerability, what is an excess for one will not necessarily be excess for another. While excess might ordinarily be defined as “more than is needed for normal body function,” that doesn’t seem to be the case with glutamate-sensitivity. Rather, excess seems to be related to the amount of glutamate that will damage or kill a given subject’s glutamate receptors.

Excess may be created by:

- Eating enough Manufactured free glutamate at one sitting to trigger glutamate receptors on vulnerable cells;

- Eating enough Manufactured free glutamate to trigger glutamate receptors on cells that had not previously been damaged or made vulnerable, and

- Adding ingested Manufactured free glutamate to stores of glutamate in the body.

Manufactured free glutamate will be found in infant formula, protein powders, protein drinks, processed food, enteral care products, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and dietary supplements. There is more than sufficient Manufactured free glutamate in processed foods to cause reactions in people who choose not to limit their access to Manufactured free glutamate.

Data on availability will be found in grocery stores. Access a list of ingredients that contain Manufactured free glutamate (https://www.truthinlabeling.org/names.html), then look for products that don’t contain them. You won’t find 10 products that don’t contain at least one of the ingredients on that list, and every one of them contains Manufactured free glutamate. Consider how many of those Manufactured free glutamate containing products are in the meals and snacks enjoyed by people everywhere. Include restaurant foods in that tally.

Glutamate receptors

Glutamate receptors receive the glutamate sent to them by glutamate neurotransmitters. Although glutamate is essential to normal body function, when present in excess outside of intact protein it becomes excitotoxic, firing repeatedly and causing cell death and/or damage to targeted cells.

If cells are protected from excess glutamate, as the brain may be protected at least in part by a robust BBB, a little excess glutamate sent their way may not harm them. But if the BBB is ineffective, targeted cells die. Outside of the brain and central nervous system, glutamate-receptors may have no protective shield from excitotoxins at all.

Relatively recently, researchers discovered glutamate-receptors beyond the brain and central nervous system. These include, but are not limited to peripheral receptors in the stomach, heart, lungs, kidney, liver, immune system, spleen, and testis. And cells associated with each may be damaged or killed if glutamate sent from glutamate neurotransmitters reaches them. It’s possible that these peripheral receptors may have some type of protection system, but if so, scientists have not yet identified it.

Years ago, it was thought to be remarkable that glutamate-toxicity worked through the brain, since glutamate could produce an immediate migraine headache. Glutamate eaten – brain triggered – headache happened within seconds. Today it is understood that glutamate can move directly to peripheral receptors without traveling through the brain.

It appears that cells that host glutamate receptors can be damaged if exposed to a little glutamate, but not enough to kill them outright. There might be times when one ingests enough Manufactured free glutamate to damage a cell, but not enough to kill it, or damage some of the cells in a group that control a particular function but not enough to knock out all of them. Ingest more glutamate on a second occasion, however, and those cells may die. Some Manufactured free glutamate sensitive people report that they can knowingly ingest Manufactured free glutamate in a favorite food on one occasion without noticing a reaction, but visibly react when that same food is consumed several days in a row.

What would increase glutamate receptor vulnerability?

Damage to the BBB would be the most obvious factor. It is known that lack of blood-brain barrier development in the fetus and infant make them extremely vulnerable to exposure to Manufactured free glutamate passed through their mothers’ diets.

Damage done to the BBBs of mature humans through use of drugs, from seizures, stroke, head trauma, hypoglycemia, hypertension, extreme physical stress, high fever, and the normal process of aging, can render them more vulnerable than others.

Individual sensitivity may also be related to the integrity of cells or groups of cells that control a particular function. A person who has experienced heart problems might very well be predisposed to experiencing cardiac-related reactions by virtue of having glutamate receptors in the heart vulnerable to insult by glutamate. A person with asthma, is likely predisposed to having an asthma attack after consuming free glutamate.

Reports from consumers tell us that intensity or severity of reactions appear to be affected by alcohol ingestion and/or exercise just prior to, or immediately following MSG ingestion, and some women report variations in their reactions at different times in their menstrual cycles.

Summary/conclusion

We have presented an overview of glutamate excitotoxicity gleaned in large part from persons who have experienced reactions to it. This is information not generally considered by those researching abnormalities associate with glutamate. Hopefully, insights generated by this information will be used by researchers probing the mechanisms of glutamate toxicity and by medical professionals working with people who react to the excitotoxic effects of Manufactured free glutamate.

1 growing or originating from within an organism.

2 originating from outside an organism.