Why is Ajinomoto trying so hard to keep transglutaminase unlabeled?

Over the past few decades celiac disease (CD) has morphed into a “major public health problem.” Along with it, other autoimmune conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis, are also topping the charts as very common disorders with dozens of heavily advertised drugs created to treat them.

If you ask why, the knee-jerk response is typically that better testing has uncovered all these otherwise undisclosed conditions. But does that really explain things? And it certainly doesn’t take into consideration what experts refer to as large numbers of people with undiagnosed autoimmune diseases, especially CD.

Back in 2015 two researchers with expertise in metabolic diseases, Aaron Lerner, a professor at Tel Aviv University, and Torsten Matthias, affiliated with the AESKU.KIPP Institute in Germany, first sounded the alarm on a largely unknown, widely used food additive – an enzyme called transglutaminase (TG). At that time, they proposed a “hypothesis” linking TG used in food processing to celiac and other autoimmune diseases. Four years later, however, the pair stated that further research and observations have closed the “gaps” in our understanding of how TG is an “inducer of celiac disease.”

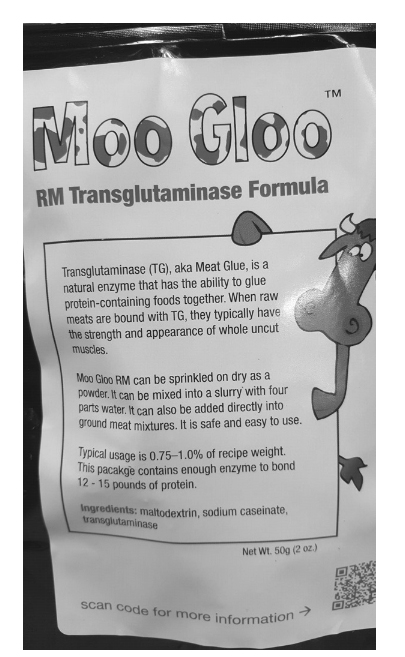

Big Food’s favorite find to ‘glue’ things together

Transglutaminase, a.k.a. “meat glue,” is the darling of Big Food for lots of reasons: it can glue together scraps of fish, chicken and meat into whole-looking cuts (often called “Frankenmeats”); extend the shelf life of processed foods (even pasta); improve “texture,” especially in low-salt, low-fat products; make breads and pastries (particularly gluten-free ones) rise better, and, as one manufacturer puts it, allow for use of things that would ordinarily be tossed out — unappetizing leftovers and scraps of food that would “otherwise be considered waste ingredients, creating an added-value product.”

But more than just turning “waste ingredients” into new food products, there are a host of other reasons why you should do your best to steer clear of meat glue.

‘Tight junction dysfunction’

The 2015 research published by Lerner and Matthias detailed how certain food additives may be behind the steady rise of autoimmune diseases due to something called “tight junction dysfunctions,” which can set the stage for a wide variety of serious ailments, calling out transglutaminase as one of the commonly used food additives that can enhance “intestinal junction leakage.”

A subsequent study in 2019 recognized transglutaminase as a “likely culprit” in celiac disease.

In 2020, Lerner and Matthias published yet another paper on transglutaminase and celiac disease, calling it a “potential public health concern” and saying that they hope their review will “encourage clinical, scientific and regulatory debates on (its) safety to protect the public.”

Despite all the warnings and additional research, use of the enzyme is booming, and all its food uses are now considered GRAS (generally recognized as safe) by the FDA.

TG and MSG

The similarities between MSG and transglutaminase are quite noteworthy. Not only is the enzyme manufactured in great quantities by Ajinomoto (as is MSG) but the way TG is promoted by the company is remarkably similar to its long-running propaganda campaign claiming that MSG is a safe ingredient.

For example, Ajinomoto states on its websites and elsewhere that both MSG and TG are “found in food naturally,” are “safe,” used in many countries and considered GRAS in the U.S. by the FDA. And just as MSG supposedly in no way causes serious reactions, the company says that TG in no way causes celiac disease – in fact, under some circumstances the TG added to food can actually help CD patients, Ajinomoto says.

While transglutaminase is found naturally in the human body (as is glutamate), there is a significant difference between microbial TG (the manufactured additive) and “our own transglutaminase” says Lerner. (Just as there is a major difference between manufactured MSG and the glutamate in your body).

That’s because the tissue TG produced in the body “has a different structure (from) the microbial sort, which allows its activity to be tightly controlled. Microbial transglutaminase itself could also increase intestinal permeability,” he says, “by directly modifying proteins that hold together the intestinal barrier.”

The FDA has “no questions”

While once the FDA pretended to look into the safety of a product before granting it GRAS status, not even that is done any more. Now a company simply turns in a statement that a product should be referred to as GRAS, and it’s done.

Starting in 1998 Ajinomoto filed four notices of “self-determined” GRAS status for TG with the FDA. The first was to use TG in seafood. In 1999 they sent in more intended uses for hard and soft cheeses, yogurt, and “vegetable protein dishes/veggie burgers/meat substitutes.” In 2000 Ajinomoto sent another notice to the FDA regarding using transglutaminase in pasta, bread, pastries, ready-to-eat cereal, pizza dough and “grain mixtures.”

And in 2002, Ajinomoto asked that anything else it might have previously overlooked, referred to as “use in food in general,” be given GRAS status. None of these GRAS notices elicited any objections from the FDA. Nothing that Big Food asks for is even questioned any more.

Included in the 2001 “everything else” notification from Ajinomoto were some details of a 30-day toxicity study using beagles. Despite findings that included dogs that had developed a pituitary gland cyst, discoloration of the lungs, an enlarged uterus and “significantly” lower prostate weights, all that was considered “incidental and unrelated” to TG. Why they bothered to include a study that shows that their product causes harm to the animals studied can only be understood if you know how Ajinomoto operates. Having done a study, they can later refer to the study that they did as though it proved that their product was “safe,” knowing that no one will challenge them. Such claims have great propaganda value.

The FDA had “no questions.”

Transglutaminase, here, there and everywhere

Lerner and Matthias have been warning for years about TG hidden in processed foods, saying it’s “unlabeled and hidden from public knowledge.” As we mentioned in another blog on TG several weeks ago, aside from “formed” meat products sold in supermarkets in the U.S. where the enzyme must be called out on the ingredient statement, TG can easily go undercover.

And Ajinomoto has even added its own tips to help food manufacturers avoid labeling by providing an explanation of how TG is just a “processing aid,” as well as making available a letter authored by a law firm in Germany stating that aside from use in “formed” meat or fish, transglutaminase is “no ingredient” and as such in the EU does not have to be included on a food label. In fact, the lawyers go so far as to state that if a substance (such as TG) is “without any function in the finished product,” listing it on the ingredient label can “mislead the consumer.”

The FDA told us that if TG is used as a “processing aid” it’s considered an “incidental additive” and is “exempted from ingredient labeling.”

Even organic products aren’t safe from TG, as TG is considered A-OK to use it in organic foods, falling under the “allowed” generic category of “enzymes” on the USDA “National list of allowed and prohibited substances” in organic food and farming.

Perhaps the most devious use of this enzyme is to improve the appearance of gluten-free bakery products. Manufactured, microbial transglutaminase “functionally imitates” natural-tissue TG, which is known to be an autoantigen (a “self” antigen, reacting to something produced by the body that provokes an immune response) in those who suffer from celiac disease.

Steering clear of transglutaminase

The TG story could very well be called a case against processed foods, as the only sure-fire way to avoid this gut-wrenching enzyme is to make/cook all your food from scratch. That being a very unlikely prospect these days, the next best thing is to avoid the following:

- Low-fat and low-salt products, especially dairy and dairy substitutes;

- Chicken nuggets, along with any other “formed” meat products;

- Expensive cuts of meat being sold much cheaper than they should be (that especially is true for restaurants);

- Sushi from unreliable sources, formed fish sticks and balls;

- Veggie and tofu burgers; and

- Cheaply produced pasta (TG is said to help when using “damaged wheat flour”).

When asked what he would consider to be an important take-away regarding transglutaminase, Professor Lerner told us that it would be for the FDA to “reconsider the classification of (manufactured) TG as GRAS.”

If you have questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you. If you have hints for others on how to avoid exposure to MfG, send them along, too, and we’ll put them up on Facebook. Or you can reach us at questionsaboutmsg@gmail.com and follow us on Twitter @truthlabeling.